Summary

- Over the past decade, Russia has re-entrenched itself in Libya, making the country the main hub of its African operations

- It has used three opportunistic processes: “cultivation” (seeding proxies), “Wagnerfication” (propping up strongmen) and “domestication” (harnessing local assets)

- To understand these is to understand Russia’s playbook for embedding itself in fragile states

- It is also to identify weaknesses European states can exploit to curb Russia’s influence in Libya, a major vulnerability on the continent’s southern flank

How Russia returned to Libya

In 2011, as the late Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi rained shells upon his citizens, Russia chose not to veto the crucial UN Security Council resolution to impose a “no fly zone” over Libya. The abstention may have been part of a genuine policy to reset Russian relations with the West. Or it may have been a ploy to rebuild Russia’s multilateralist credentials, divert Western powers into more Middle Eastern misadventures, and make space for Russian interventions elsewhere. Either way, since Vladimir Putin reclaimed the Russian presidency in 2012, his misrepresentation of this episode as a betrayal by NATO—which he says abused Russia’s abstention to conduct unilateral regime change in Libya—has become part of the origin story for his crusade against the West.

Whether or not Putin was genuinely sore about Qaddafi, Russia’s position in Libya deteriorated in the revolution’s aftermath. Libya’s new authorities cast Russia as an enemy of the Arab uprisings, depriving it of roughly $14bn in weapons, oil and construction deals. But in 2014 Libya descended once more into civil war—and it was in that unfolding chaos that the dormant Russia-Libya relationship began to stir from its slumber.

*

One goal of Putin’s foreign policy has always been to reaffirm Russia’s status as a great power. His attempts to do this over the past decade, antagonistically to Europe and the West, have perhaps been most visible in their flashpoints: the war in Syria, for example, and the all-out invasion of Ukraine. These are also the fronts where the United States and European countries have pushed back.

But Russia has more quietly re-entrenched in Libya over the past decade, and in so doing has met far less resistance from the West. Now, Moscow once again enjoys powerful influence in this troubled but strategically pivotal Mediterranean state. Russia’s presence extends from Libya’s north-eastern coastline to its south-western Sahelian borders. Russian forces maintain this presence via proxies, notably the eastern Libyan dictator Khalifa Haftar, from five military bases dotted through the country. These forces are also present, and wield influence over, Libya’s southern oil fields and eastern oil terminals. Russia has used all this to help Haftar’s putative heir, Saddam Haftar, expand Libya’s role as a hotspot for smuggling: of weapons, drugs, fuel—and people.

Libya’s lawlessness has thus proven valuable for the Kremlin. So much so that the country has become a forward operating base to help Russia deploy fighters and equipment to other theatres (and extract assets from them). It was telling that after the fall of Moscow’s Middle Eastern proxy, Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, in December 2024, Russia simply relocated many Syrian assets to Libya. Syria remains vital to Russia; hence Moscow’s swift pivot to working with the new authorities in Damascus. But by the end of 2024, Libya was Moscow’s main hub to feed its African operations.

This paper examines the gambits, tactics and strategies the Kremlin deployed to re-embed itself in Libya under Europe’s nose. The patterns it uncovers in the past ten years of Russian engagement in the country make clear that this was far from a “masterplan”. But they also provide a window onto the evolution of Russia’s foreign policy since 2014. Indeed, this paper shows that Russia’s re-engagement in Libya took place over three phases that add up to a playbook for Russia embedding itself in and exploiting fragile states. These are:

- Cultivation: Seeding potential proxies through a range of influence groups, sowing fertile ground for deeper interactions in states where Russia lacks pre-existing relations;

- Wagnerfication: Deploying Russia’s foreign intelligence agency the GRU (previously under the banner of the “Wagner Group” and other such fronts) to entrench in a country by helping a proxy, usually a struggling strongman;

- Domestication: Using increasingly open control over that proxy and a country’s assets to advance Russian interests, often to the severe detriment of the country (and European security).

Over the course of these different approaches in Libya, one constant in Russia’s tactics has been patient opportunism to continuously deepen its entrenchment. Another has been its quest for openings to develop its relations with powers such as Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), all the while undermining Europe and the West. It has done this by militarily, diplomatically and politically assisting Haftar and other proxies such as Saif al-Islam Qaddafi (Muammar Qaddafi’s son, now wanted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity) to increase their influence in Libya, but also their dependence on Moscow. Russia then moved through these proxies to effectively claim and exploit military bases, oil infrastructure and smuggling routes.

But Russia’s hold in Libya remains moored to the fate of its proxies. Unlike other intervening states—notably Turkey, which is a key backer of Libya’s internationally-recognised government in Tripoli—Russia has no legal military presence in Libya. This means that Russian power there still depends on Libya remaining in its state of transition. Leaders in the Kremlin are reportedly working to correct this by seeking to lease a naval base in Libya’s far eastern port city of Tobruk. It is also developing relations around the government in western Libya and trying to shoehorn its proxies into positions of legal authority.

The ins and outs of the past decade of Russian influence in Libya thus also reveal the frailties of the Kremlin’s approaches, and how the very European countries it works to undermine could displace its chaos-exploitation activities.

European policymakers are juggling many competing and urgent priorities. But whether they like it or not, Europe’s strategic competition with Russia extends to the southern neighbourhood. Displacing Russia from Libya would have knock-on effects throughout this competition. It would close off vital funds for its aggression in Ukraine. It would also obstruct Russia’s efforts to fuel Sudan’s civil war. And it would hamper Russia’s attempts to flip African states against Europe, helping to redefine the global competition for critical raw materials and undermine Russia’s entire Africa strategy.

European countries need to start by making Russia’s deployment more costly for Moscow. They should do this by combatting the smuggling activities it is linked to, as well as developing new legal tools to fight Russia’s network of private military companies (PMCs). In Libya, Europeans will have to degrade Russia’s proxies and press key regional actors to stop facilitating destabilising Russian activity.

But they will also need to offer a vision of their own. They should aim to build coalitions with Russia’s current partners and work with them to secure a safer space for all to pursue their interests. This feeds into the longer-term goal of shepherding Libya towards a unified, legitimate government that would ideally call for Russia to leave. And at the very least it would dilute Moscow’s influence and strengthen both Libyan independence and Libya’s capacity to resist Russian-inspired criminal activity.

A fragile “entente roscolonial”

The story of Russia’s return to Libya begins with its post-2007 moves to reemerge as a great power after the blows of the 1990s—and more specifically its moves to dominate the south-eastern Mediterranean basin as part of that comeback.

For example, Russia tried to fill the void the US left when it froze military aid to Egypt after President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi’s bloody coup in 2013. Then in 2015 Russia went all-in to defend its last warm-water naval base at Tartus in Syria, invoking its “regime change” narrative about Libya to shield Assad and other Russian interests in the country from UN-led humanitarian interventions in the war there. By entrenching its power in Libya, Moscow would benefit further. It could tap the country’s vast energy potential. One UK intelligence source also claimed that Moscow explicitly wanted to trigger further waves of migration towards Europe.

In February 2022 Russia’s attempted full-scale invasion of Ukraine galvanised the Kremlin’s antagonism towards the West. Unlike in Crimea in 2014 or for its crimes in Libya, this time the West held Russia accountable for its violation of international norms. Russia’s violation was also condemned by multiple resolutions at the UN General Assembly, underlining the weakness of Moscow’s multilateral politicking compared with its Western rivals. Putin’s diplomats subsequently moved more aggressively to case Russia as the geopolitical antithesis to the West; a role in which it aims to build mutually beneficial partnerships with the “world majority” and “democratise” the world order.

According to Russian foreign policy experts, in a practical sense, this means leaders in the Kremlin currently see the world as a collection of pro-West, pro-Russia or agnostic states, seemingly based on a country’s position in the Ukraine war.[1] More generally, it gives Russia a geopolitical stature far beyond what its economic, military or cultural power might ordinarily allow. It also creates, ironically, colonialist opportunities for Russia to increase that power.

Accordingly, the Kremlin seems to have divided the world into clusters, developing bespoke tools to maximise the benefits of different groupings and countries. Although it is unspoken, Russia’s “new world” appears to be stratified into those with which it can partner to build alternative global systems (like the UAE); and those it can exploit enhance its own status (like Libya). The latter countries are usually marked by the presence of the network of shell companies formerly known as the “Wagner Group” (alongside other PMCs).

Wagner politics was a vehicle for Russian entrenchment that usually involved propping up weak strongmen in exchange for asset control. Despite its presentation as a PMC, mercenaries were always technically illegal in Russia; and there was never a single entity named “Wagner”. The label “Wagner Group” was itself an abstraction that referred to a network of companies that sprung up, often ad hoc, to provide political engineering, military assistance and resource extraction services where Russia was building its influence.

Despite their protestations, the Russian presidency and senior GRU officers always had close control over Wagner activities. Soldiers joining Wagner and related PMCs (which this paper will group under “Wagner”) sign contracts with GRU “Unit 35555”, a laboratory for socio-psychological research. Besides the GRU, the network was cohered and unified by the late Yevgeny Prigozhin as a financier and central administrative node; and characters such as the (also late) neo-Nazi Dimitry Utkin were the military link. Utkin’s nom de guerre “Wagner” gave the group its name.

Prigozhin’s mutiny in mid-2023 was a show of discontent towards Russia’s ministry of defence that span out of control. Following Prigozhin’s and Utkin’s deaths in a plane crash shortly after, the Kremlin dropped the pretence entirely and removed the layers of abstraction. It named the new body it formed to oversee this process “Africa Corps” (seemingly after the Nazi field marshal Erwin Rommel’s “Afrika Korps”).

Russia benefits economically from the assets of Wagner-linked states, and from the group’s military gains by using its men as mercenaries. These fragile states are becoming increasingly interconnected, in what some analysts have dubbed the “entente roscolonial”. All the while, Moscow broadcasts a revolutionary propaganda of helping to “fix what the West broke”.

Whether by happenstance or design, in 2025 Libya is the operational hub of Russia’s Africa cluster. The military bases Wagner commandeered —at Tobruk, al-Khadim (Benghazi), Ghardabiya (Sirte), Jufra, Brak-al Shati (in Libya’s south-west) and the newly developed Maaten al-Sarra (near the border with Chad)—are the logistical hubs Russia uses to support its other African deployments. These bases form part of an airbridge that helped arm the attempted putsch by Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in April 2023 and sustain the country’s devastating civil war ever since. Troop movements and flights over 2024 indicate that Russia’s bases in Libya have become indispensable in maintaining its nascent deployments in Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso as well as its prolonged presence in the Central African Republic.

Alongside this, Haftar has become a diplomatic asset, used to provide Libyan support to Russia’s African acolytes. Moscow’s proxy sent one son, Sadeeq Haftar, to Khartoum with $2m for the RSF leader on the eve of Sudan’s civil war in 2023. Another son, Saddam Haftar, was dispatched to tour the Sahelian outposts of the entente over 2024 with a view to formalising a diplomatic alliance. These military partnerships helped the Nigerien junta under Abdourahamane Tchiani and Chad’s leader secure lucrative cross-border smuggling routes.

In early 2025 Khalifa Haftar even visited Belarus. It seems Russia is using Belarus as cover to help upgrade Tobruk’s Gamal Abdul Nasser military base—which Moscow likely aims to make its new Mediterranean naval headquarters after Assad’s fall put its Syrian base at risk. The wide range of cooperation discussed in Minsk is seemingly a channel to inject Libyan money into Belarus in exchange. This underlines how Russia can use Libyan finances and the fig leaf of Haftar’s military to strengthen its non-African Russian allies.

Underpinning Russia’s new Africa infrastructure is a smuggling network that Wagner presumably guided Saddam Haftar to build. Through this the Kremlin exploits (and exacerbates) Libya’s lawlessness to circumvent European sanctions on fuel exports. It also destabilises Europe and the US through the weaponisation of migration; smuggles fuel and arms to other African proxies; and, of course, makes plenty of money.

The rebrand from Wagner to Africa Corps does not change the fundamentals. Even the Nazi connotations of the name have remained, along with the group’s longstanding disinformation function. The biggest change is in the governing structure. The Kremlin has effectively shortened the leash between Putin and the operatives on the ground—formalising the Russian presence in Libya. The price of this is a loss of plausible deniability. But in a post-Ukraine world where the UN Security Council is effectively frozen, and Putin has an ICC arrest warrant against him, that is no longer so important. In a post-Gaza world, in which the US president has imposed sanctions on the very same court, it matters even less; especially not to Putin’s strategic narrative that he is battling to democratise the world-order against US imperialism.

But, as the story of Russia’s re-entrenchment in Libya will show, Moscow is not in as comfortable position as it seems. The shift to Africa Corps was a consolidation. Putin will inevitably miss the initiative Prigozhin brought to enable such a rapid and creative rise in security partnerships and business relationships. Russia is already struggling in Burkina Faso and Mali; it seems to have few ideas to stabilise Libya beyond attempting to nudge its proxies into formal positions of power (essentially, to recreate the Assad scenario). Given the predatory, extractive and fractious nature of all these proxies, that is more likely to worsen than end the chaos.

Now is the time for Europeans to extract Russia’s Libyan linchpin. The three phases through which Russia achieved its status in Libya show how the Kremlin feels out opportunities to develop proxies. They reveal how it can then entrench itself and ultimately hijack a nation to pursue its geopolitical goals. But they also show how Russia’s vacuum-filling is unsustainable and destructive. Europeans will have to learn from this to compete with Russia in the confrontation Putin has forced on them.

Cultivation: How Russia enters geopolitical vacuums

A bear knocks at the door

In 2014 Russia had to regrow its influence, almost from scratch, in a new Libya that was fracturing politically, economically and militarily. The Kremlin encouraged groups of Russia’s elites to approach Libyans from their respective angles: politicos doing diplomacy, oligarchs conducting economic outreach, and the ministry of defence overseeing military partnership building. Russian foreign policy experts have since described this process as a competition to see who could bring the best prize back to Putin.[2] Intentionally or not, the result of this scoping exercise was a platform on which Russia could build more complex foreign policy.

Setting the table

The diplomatic track was heavily influenced by Ramzan Kadyrov. The Chechen leader had worked closely with Putin on Middle East policy since the early 2010s, acting as something of a cultural envoy for Russia thanks to longstanding connections between the region and Chechnya.

In 2015 Kadyrov picked a close associate, Lev Dengov (a career diplomat with previous experience in Libya) to lead the new “Russian contact group for intra-Libyan settlement”. This would become the Russian foreign ministry’s official vehicle to engage with Libya. The contact group was a mission focused on Libya’s Tripoli-based and internationally recognised government of national accord (GNA). To supplement this, Russia used Kadyrov’s links with Islamist and old revolutionary armed groups to expand its network across western Libya. This allowed Russia to set itself up as a mediator between Libya’s warring parties and helped ensure it a place in the UN-led political process to reunify the country. In March 2017, then GNA president Fayez Sarraj visited Moscow, the Kremlin used the visit to push its narrative on how the West broke Libya and pose as the one who would fix it. It was also an opportunity to get Sarraj to promise to review the Russian contracts that were lost in 2011 with the fall of Qaddafi.

Also competing for Putin’s approval were an assortment of oligarchs and business figures with commercial ties to Libya. They helped economically re-establish Russia across Libya and leverage the value of the former contracts to develop political allies who could restart frozen projects.

But the most successful of Putin’s men were those from the ministry of defence.

In 2014 Russia had reached out to militia leader Ibrahim Jathran, who then controlled Libya’s lucrative oil crescent, an eastern coastal area rich in hydrocarbons. Jathran had blocked Libyan oil exports, holding the country to ransom in a power move he justified as a demand for more equitable division of oil revenues. In a deal that would have turned this opportunistic yet small-time militia leader into a serious national force, Russian agents offered Jathran weapons and help to illicitly sell oil and get into government. According to Russian foreign policy experts, the Kremlin places great value on monogamy in its proxies. Moscow accordingly demanded to be the militia leader’s sole foreign backer. This was also an apparent attempt to develop an exclusive partnership on valuable Libyan real estate. Ultimately, Jathran backed out following pressure from other intervening states.

Since Haftar—then a disgraced Qaddafi-era “general”—returned from exile in the US in 2011, he has attempted several coups in Libya. So far, after years of gruelling military campaigns and thanks to considerable foreign support, he can claim control of Libya’s eastern province of Cyrenaica and its southern province of Fezzan.

In May 2014 Haftar launched “Operation Dignity”, a key formal trigger for Libya’s first post-uprising civil war. The general advertised this as a push to purge extremists from the eastern city of Benghazi, following assassination campaigns that had plunged the city into fear, and which he entirely blamed on his enemies. Haftar managed to rally former regime officers and eastern tribes to create a new military force, the “Libyan Arab Armed Forces” (LAAF).

The LAAF was an expression of its external backing. Egypt helped Haftar design his army and the UAE provided the funding, technology and know-how. Both regional powers had also cultivated his failed coup against Tripoli in February 2014 and then drove his subsequent military operation on from behind. Haftar’s operation thus opened a Libyan front in a Gulf-driven counter-revolution to revert the Arab world’s nascent democracies to authoritarian rule, one that Sisi had begun in Egypt the previous year.

Haftar and his band of former officers were familiar with Russia, having trained at the Soviet Frunze Military Academy. But the general, with his strong ties to the West, was far from the unclaimed prize Jathran would have been. Russia would also have likely hesitated to take a side in what the Kremlin perceived to be a regional spat: with Egypt, the UAE and Saudi Arabia supporting Haftar; and with Turkey and Qatar considered to be behind a rival, Islamist movement called “Libya Dawn”.

Accordingly, Russia’s initial support for Haftar was low-key. In the first two years of Operation Dignity, Russian arms were quietly air freighted in cargo planes to Tobruk on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast. Russian Sukhoi, Mi-8, and MiG-21 military aircraft appeared in the country to join Haftar’s ageing Soviet fleet, as did military trainers, technicians and advisers. Russia provided all this in cooperation with the UAE and Egypt.

Indeed, that the support happened at all was likely down to Moscow’s willingness to trade exclusivity for an opportunity to strengthen Russian relations with those regional powers which were considered more important than Libya, like the UAE. This became the foundation of a military alliance between Moscow and Abu Dhabi that would later flourish, helping to ignite more civil wars in Libya, then in Sudan, and later fuelling Russia’s push through the Sahel. Simultaneously, Moscow used its official contact group in western Libya, via Dengov, to maintain plausible deniability and claim that Russia’s position was support for the UN-led peace process (and the ongoing 2011 Security Council arms embargo).

Boiling the kettle

From 2016 Russia’s quiet support for Haftar began to get much louder.

In May the Russian mint Goznac printed 4bn dinars ($2.9bn) of a counterfeit Libyan currency to provide liquidity to Haftar’s cash-strapped operation. It did this through a parallel central bank inaugurated by Libya’s parliament, the House of Representatives, which sat in Haftar-controlled Tobruk. Despite protestations from the GNA and Western governments, given that these notes differed from Libya’s official currency printed by Britain’s De La Rue, the GNA eventually accepted the Russian bills as Libyan tender. This was likely because not doing so could have led to completely divided economic systems that would be near impossible to reunify.

In June Haftar visited Moscow, where he met defence minister Sergei Shoigu and security council secretary Nikolai Patrushev. The general used this first Russia visit to formally request more advanced weapons systems and replacements for the LAAF’s ageing aircraft. Haftar’s spokesman hailed the trip as a successful formalisation of the relationship. The agreements reportedly included weapons maintenance and air defences, and enabled the LAAF to claim frozen Qaddafi-era arms contracts.

For its part, the Kremlin publicly maintained that Russia could not re-activate weapons contracts until the arms embargo was lifted. But the claims of Jathran’s lieutenants when Haftar swept the oil crescent in September 2016 suggests advanced weaponry was being transferred regardless. These claims were corroborated by new munitions such as Russian-made guided artillery shells suddenly appearing in Haftar’s battles. Having gained control over Libya’s reactivated oil terminals, Haftar was emboldened to push for more. In September, he anointed himself with the rank of field marshal. Shortly after, he dispatched an ambassador to Moscow to request a Syria-style intervention. Haftar then returned himself in November, allegedly offering Russia an airbase near Benghazi if it could get rid of the arms embargo.

A few things were likely behind the romance of 2016. Firstly, Moscow had failed to secure exclusivity over any military proxy. Jathran was a busted flush. The western Libyan armed groups Kadyrov had engaged were working closely with the US, Britain and Italy in a military operation to free the central city of Sirte from the Islamic State group. Secondly, the Haftar project helped Moscow show it could be a practical friend to the America’s most active regional partner, the UAE. Moscow had also managed to deepen relations with Cairo in its bid to to secure rights over Sidi Barrani, a Soviet-era airbase on Egypt’s far western coastline. Conveniently enough, the Sidi Barrani airbase was also a significant platform for Russia’s stepped up assistance to Haftar, just as Russia deployed special forces to the Egyptian base.

Perhaps most importantly, though, Russia was far from the only intervening power claiming to support the UN while developing its own proxies and securing its interests. International norms around Libya were being chipped away by a multitude of states pursuing their own gains. France, for instance, was actively supporting Haftar and flouting the arms embargo alongside Egypt, Russia and the UAE, believing only a strongman could bring stability to Libya’s multitude of militias. It found itself against Italy, which was cooperating with western Libyan authorities and militias in the hope that this would stop hundreds of thousands of migrants from crossing the Mediterranean and ending up on its shores. The UK and Turkey also sided with the western, internationally recognised authorities.

This rejection of the rules-based order for unilateral interventions around individual actors and forces diminished Libya’s potential for political progress. Europeans had also validated a game they could only lose against states willing to use force and violate norms more flagrantly. Russia favoured this game. In the words of Gerald Feierstein, a senior US diplomat for the Middle East, Putin was “pushing the envelope” and would keep doing so “until he was stopped”.

Putin was not stopped. But Russia would have to shift its focus to deepen its engagement in Libya. Haftar’s “love-bombing” of Moscow over 2016 could not alter the fact that lifting the arms embargo was practically impossible. Libya was still divided, Haftar was still warring in Benghazi, and he was still detested by western Libyan groups. The returns for the Kremlin had seemingly plateaued. Compared with the UAE and France, Russia remained a junior partner in Haftar’s military coalition. And there would be no Russian base in Egypt, as the newly inaugurated US president—one Donald Trump—worked to improve relations with his “favourite dictator”, President Sisi. So, it seems that Russia pivoted from proxy building to pursuing formal political engagement. This is a pivot that would reappear multiple times over the coming years.

Sparkling conversation

The GNA’s mandate was set to expire in December 2017. Russia’s response seems to have been to attempt to mediate a political deal to form a new government and formalise the LAAF as Libya’s army. This would have given Haftar and his Soviet-trained officers a powerful role in the country’s institutions. In January 2017 Russia granted the field marshal the military honour of being received on its aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, where he spoke again with Shoigu and received assurances of more military support. Alongside this, Moscow increased its contact with the GNA and political and military forces from Misrata on Libya’s north-western coast. But the Kremlin never got the chance to turn these flirtations into a summit.

In July 2017 the French president Emmanuel Macron pipped Putin as a mediator, convening Haftar and Sarraj at La Celle St Cloud in France where they agreed a roadmap towards elections. Haftar, for his part, roundly ignored the roadmap to continue with his conquering. He also wooed the Kremlin back towards him with promises of oil from the crescent Russia had helped him seize. Still constrained by the same limits on arms transfers, however, Russia’s ministry of defence would have to give way to the less conspicuous GRU.

In May 2018 Wagner appeared in Libya for the first time, helping Haftar storm Derna—the last city in eastern Libya outside his control. Haftar was apparently so pleased with this support that he returned to Moscow on November 10th to catch up with Shoigu and, more notably, Prigozhin.

The meetings in Moscow came during the build-up to Italy’s November 12th “Palermo Conference”, through which Rome aimed to jumpstart the stalled Haftar-Sarraj agreement from La Celle St Cloud. But Moscow’s mercurial friend made life difficult. Indeed, he prevaricated over whether he would attend at all, confirming only at the last minute, and then arriving more than an hour late. Haftar also refused to attend plenary sessions, instead insisting on a “mini summit” with Sarraj, Sisi and Russia’s then prime minister Dimitry Medvedev. The Russia-Egypt-Libya breakout room pointedly excluded Turkey (which at that point was at odds with Russia in Syria and a key regional rival of Egypt and the UAE). This exclusion promptly turned the mini summit into a mini diplomatic scandal, as Ankara’s delegation stormed out of the conference altogether. Later Sarraj would pull Medvedev aside and complain about Russia’s destabilising support for Haftar.

Russian military flights to Libya had peaked alongside Wagner’s deployment as Haftar consolidated in the east and moved south. The field marshal had been struggling to operate around or gain control of the National Oil Corporation (NOC), Libya’s sole legal seller of crude. But Wagner already had expertise in helping Assad in Syria illicitly sell oil, generally offering military assistance in return for shares in local assets. This suggests Haftar was attempting to keep his promises to transform control of the oil crescent into sales.

This indicates another shift in Moscow’s tactics: unable to claim an exclusive proxy or distinguish itself as a mediator, the Kremlin would use Wagner to entrench around Libya’s assets and use them to serve Russian interests.

Cultivation in the roscolonial

Europeans can learn a lot from how Russia re-established itself in Libya: from better understanding how the Kremlin opens up unfamiliar states to its influence, to the need to create robust diplomatic processes and the importance of protecting international norms and alliances. Indeed, the early stages of the second Trump presidency suggest that Europeans should view these less as lessons to take in gradually and more as a long-overdue cramming session.

Russia’s re-entry into Libya was a masterclass in how to fill a vacuum—even if it was in pursuit of an inherently destabilising goal. The network of elites Russia deployed demonstrates the breadth of tools Russia can apply to grasp such opportunities. Kadyrov was a cultural envoy of sorts; the oligarchs offered an avenue with corrupt autocrats and influential business figures; the ministry of defence provided an attractive vehicle for relationship building with local military actors, given Russia’s powerful military reputation.

The series of coups in the Sahel over the past few years have provided ample opportunity for Russia to deploy its military leverage. Russia has most successfully built relationships with African partners who have performed such coups, like Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traore; or helped others towards coups of their own, such as the junta in Niger and Sudan’s RSF. Of course, this relationship-building depends upon bypassing any sort of rules-based order, which Europeans could not police in Libya because key states like France were also supporting Haftar.

But looking back, Russia’s re-entry into Libya also provides insight into the processes by which Russia’s relationship-building continues towards client relationships and entrenchment. If the US and European governments had better policed the arms embargo, then Russia would not have been able to develop a foothold in Libya. Nor could it have benefited from its Libyan scoping exercise to build relationships with vital partners of the West such as the UAE.

It was in this context of impunity that Russia introduced Wagner. The result was Haftar being empowered to counter Macron’s electoral process and undermine the Palermo conference. Europeans’ own involvement with Haftar and their struggles to build a meaningful Libyan or international constituency around their conferences gave Russia and Haftar the space to do this.

Wagnerfication: How Russia harnesses struggling strongmen

The Devil’s bargain

The story of how Wagner entrenched around Haftar suggests a transition to a more direct route for the Kremlin to secure its in-country interests. The forcefulness of this route was probably tempered by Russia’s enthusiasm for its relations with its new friends: Egypt and the UAE. Underneath it all, however, the lifeline of Russia’s involvement in Libya was still the same cargo planes. And they were still traversing the same routes, in violation of the same arms embargo, as they had from the start.

Planting the idea

It did not take long for Wagner to begin a disinformation campaign in Libya to dominate the country’s already poorly regulated and managed information space. Unsurprisingly, Wagner’s Libya operations mimicked the tactical modus operandi of Prigozhin’s infamous Internet Research Agency.

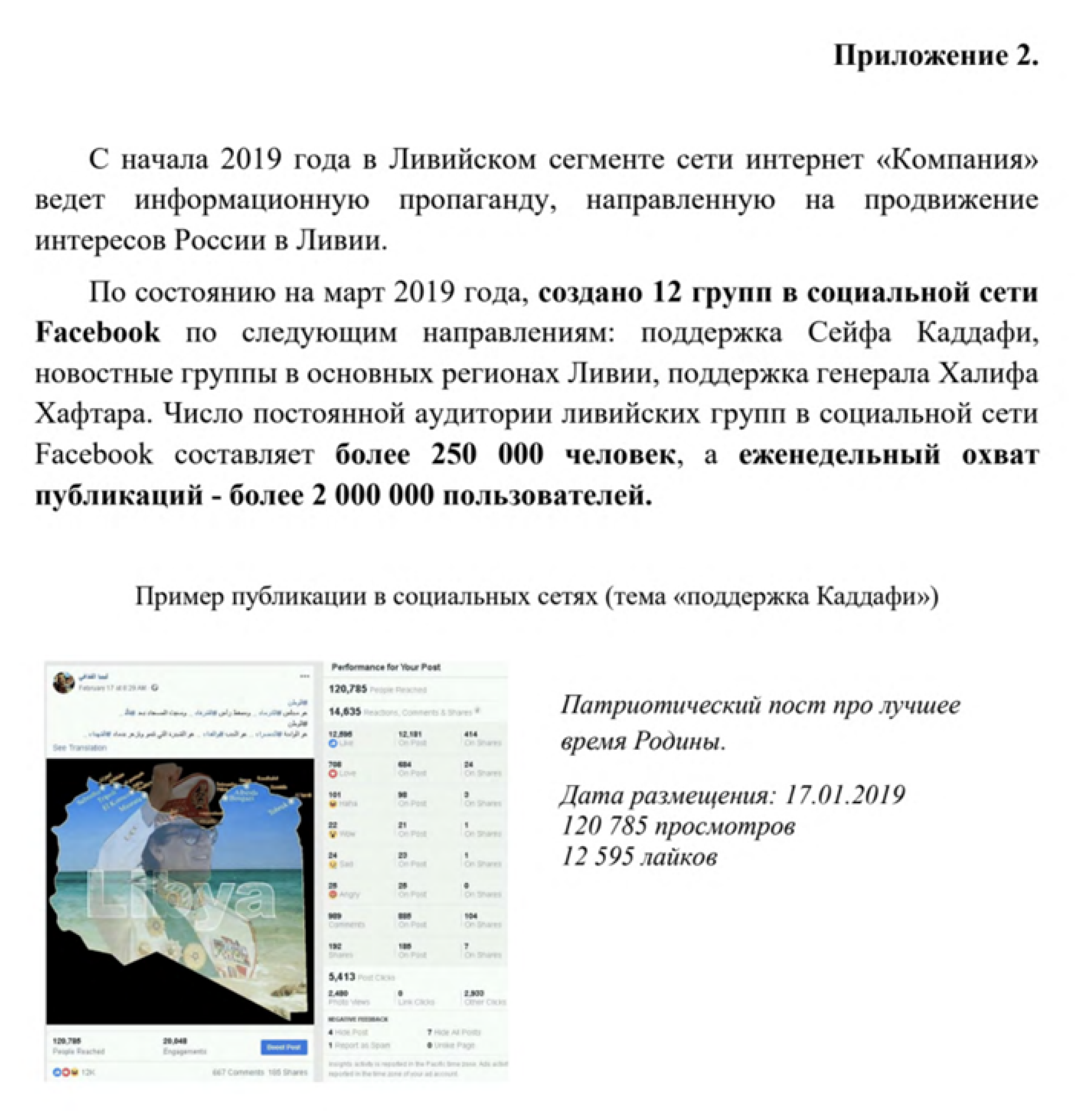

Facebook was the primary communication platform for over two-thirds of Libyans. From December 2018 onwards Wagner created a network of interlinked news sites and “social-first” Facebook pages that focused on memes and live videos. The pages were run by administrators in Egypt and managed by Russian-trained reporters alongside Libyan subcontractors. This complicated the task for Libyan authorities and even international investigators to track which pages featured Russian involvement. Wagner’s use of Libyan consultants also allowed it to pick up and sensationalise local grievances to polarise audiences, creating impassioned followers who could then be conditioned into adopting Russian-devised narratives.

The Facebook-trialled content then branched out to other social media platforms, along with private WhatsApp and Telegram groups. These activities clustered to create the impression the Wagner-promoted views were widely supported, manufacturing highly impactful echo chambers. The pages also adopted savvy social media engagement tactics, using features like competitions, feedback forms, and Facebook Live videos to develop close relationships with their audience.

The network of different organisations that hosted these pages illustrates how useful the decentralised system of ad-hoc companies was for masking Wagner activities. When leaked documents exposed the Libya operation, Facebook uncovered similar networks in the Central Africa Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Mozambique and Sudan.

Haftar himself proved more problematic. In early 2019, Wagner assessed Libya’s socio-political scene through one of Prigozhin’s agencies and found the field marshal wanting. The report derided Haftar’s expansion in Libya as simply “bribing local tribes for the right to plant the [LAAF] flag”, likely using the billions Goznac, the Russian mint, continued to print. Wagner’s report also found that Haftar was pushing powerful western Libyan groups (such as the Misratans) to unite against him, as well as isolating former allies like the Tebu tribes of southern Libya. Most concerningly of all for Moscow, the report concluded that Haftar was simply using Russian assistance to boost his profile and strengthen his ties with the likes of France and the US.

A crucial UN conference to organise elections was set to take place in April. Wagner opted to boost the political profile of Saif al-Islam Qaddafi, the old dictator’s son, as a counterbalance to Haftar (who by the end of March was advancing in western Libya towards Tripoli). Then they could use the disaffected Tebu along with mercenaries from a new alliance Wagner was developing with the RSF in Sudan to build Saif an army that could displace Haftar. But Wagner’s first meeting with Saif revealed him to be delusional, narcissistic and irrational. Saif thought Haftar was his biggest threat. But he also believed that, as soon as he went public, Haftar’s officers would simply abandon the LAAF for him. Clearly, this candidate would also need some work.

By March 2019, Wagner’s disinformation operation had grown to 12 Facebook groups. These included pro-Haftar, pro-Saif and highly localised news sites that boasted audiences of over 250,000 and had a weekly penetration of up to two million users. This meant that Russian narratives were hitting just under one-third of Libya’s population of 6.5 million. That same month, a Prigozhin-linked firm bought a 50% stake in the former state-run, pro-Qaddafi al-Jamahiriya TV station. It also created a pro-LAAF newspaper and officially consulted with the pro-Haftar al-Hadath news organisation. One key line was that “the UN is failing in its goals for Libya”.

In May 2019 three operatives linked to a Wagner-linked troll factory were arrested in Tripoli, accused of electioneering on behalf of Saif. But by then Haftar had begun a full assault on Tripoli, loosely Libya’s second post-uprising civil war. This would disrupt the very UN process supposed to lead to the elections Russia aimed to engineer in Saif’s favour.

Summoning a demon

Only Russia publicly protected Haftar following his attack on Tripoli, vetoing an April 7th Security Council resolution that would have condemned the field marshal’s offensive—though France and the US implied they would if Russia did not.

The Russian cargo planes used by the UAE during Operation Dignity to deliver Russian ammunition to Haftar’s forces were now chartered by the UAE and Egypt. They sent three planeloads a day carrying up to 500 tonnes each of Russian ammunition to Haftar’s profligate forces.[3] Tripoli’s defenders noted the use of advanced Russian weaponry such as anti-tank Kornet missiles being used to devastating effect, likely again delivered through other partners such as the UAE.[4] Separately, Russia sent journalists to Benghazi to help the propaganda effort.

Back in April, Wagner had assessed Haftar’s chances of taking Tripoli as “nil”, noting that the field marshal’s diplomatic support from France, Russia and the US had made him delusional. Despite the extensive support, Haftar had overcommitted on the battlefield and was already being pushed back. The LAAF’s command and control was comically unprofessional, to the extent it shot down its own aircraft. According to Wagner’s assessment, “The plan to ‘wear down’ Sarraj’s army […] has actually been turned into the attrition of the [LAAF] itself”. Only massive investment from the UAE, including the deployment of Chinese Wing Loong drones allowed Haftar to maintain a stalemate, while Moscow bided its time.

As autumn approached, Haftar’s alliance was crumbling. High casualties had provoked dissent among the eastern tribes that once made up the bulk of his rank and file. Tribal fighters from the south were gradually abandoning the front having been mis-sold a quick war and easy riches.[5] There was dissent in the ranks, and despite billions of dollars in armaments from Haftar’s backers, along with months of air superiority thanks to the drones, the field marshal had not made any meaningful progress into Tripoli—in fact he had even lost his forward operating base to the GNA two months into the assault.

But from September 2019 Russia dramatically increased its military assistance. (US intelligence sources would later claim that the UAE had financed Wagner’s deployment.)

At least 122 operatives were dispatched to the Tripoli front, including 39 specialist sniper teams.[6] Russian air force planes flew them and their equipment directly from the UAE to Emirati controlled airbases in Libya.[7] The operatives quickly claimed the al-Watiya air base in Libya’s western Nafusa mountains, where they deployed an SU-22 fighter-bomber. This sowed fear in the ranks of Tripoli’s defenders. The combination of airstrikes and attack helicopters launched from al-Watiya (along with more competent soldiering) allowed Haftar to finally progress into Tripoli’s suburbs. By the end of November at least 24 Wagner operatives (including a senior commander) had been killed.[8] But hundreds more were arriving.

Russia’s sudden intervention also made the LAAF more strategic. On September 16th airstrikes hit key GNA defences in Sirte: the western gate to the oil crescent; a central node of Libya’s east-west coastal road; and a main route south, through the major LAAF-controlled airbase at Jufra. This was the beginning of an operation to soften up the city that marked the east-west divide between Haftar and the GNA.

Following the airstrikes, Misratan forces guarding Sirte were gradually dragged to buttress Tripoli’s defences against the Wagner offensive. Then on January 7th 2020, the LAAF seized Sirte in a lightening raid involving feints, misinformation and a level of tactical sophistication previously alien to Haftar’s force. Taking Sirte granted Wagner access to another airbase, Ghardabiya. It also provided Haftar with the security to shut off Libya’s oil exports (the financial lifeline of Tripoli’s defence). Around the same time as the LAAF took Sirte, Russia imported a unit of Syrian mercenaries—flown from Damascus to Benghazi on Syria’s Cham Wings airline.[9]

In western Libya meanwhile, Turkey had signed a memorandum of understanding with a desperate GNA. The Turkish army accordingly took defensive positions in western Libya. The memorandum provided the GNA with Turkish security guarantees, in exchange for a deal to delineate maritime boundaries between the two countries—likely a diplomatic gambit by Ankara to boost its position in the eastern Mediterranean. This was the gamechanger that defined the battle for Tripoli (and what came after it). It also created a new foil in Libya for a rising Russia.

Making deals at the crossroads

Having become Haftar’s main military force, the Kremlin pivoted back to mediation. A day after Sirte fell, Putin met his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan. They promptly issued a joint call for a ceasefire to start on January 12th 2020. As the date approached, Wagner operatives and their accompanying RSF mercenaries were seen evacuating the Tripoli front for Jufra airbase. Then on January 13th Putin summoned Sarraj and Haftar to Moscow for formal ceasefire negotiations based on a pre-prepared agreement that would see Haftar largely return to the status quo ante positions of April 2019, but keep Sirte.

With hindsight, this looks like a gambit by Turkey and Russia to assert themselves as the core foreign parties to Libya’s conflict and displace Europe’s mediating role. Italy had attempted to hold talks with both Haftar and Sarraj in the days before the Putin-Erdogan summit. But Sarraj had pulled out at the last second, frustrated by what he perceived as European bias towards Haftar. Germany, meanwhile, was working with the UN to host a multilateral conference in Berlin on January 19th to agree a ceasefire and an end to foreign intervention in Libya.

But Wagner’s original analysis of Haftar proved astute. While Sarraj signed up to the deal in Moscow, Haftar refused to give up his hard-won positions in south Tripoli and its environs. His intransigence was allegedly encouraged by the Emirati advisors who never left his side in Moscow and who believed the deal gave Turkey too many concessions. That evening Haftar stormed out, ceasefire unsigned, humiliating Putin.

The field marshal pulled a similar stunt in Berlin a few days later, leaving Germany’s then chancellor Angela Merkel awkwardly trying to entertain a room of world leaders, stalling for time as Haftar refused to commit to a ceasefire.[10] The UAE, which had signed up to the Berlin conference conclusions pledging to respect the arms embargo, immediately increased its weapons deliveries to Haftar, freighting 3,000 tonnes in the subsequent two weeks. Erdogan, for his part, pledged to “teach [Haftar] a lesson”.

By the end of April 2020, that lesson was well under way. Haftar had been expelled from Tripoli’s suburbs and was quickly losing territories west of the capital. For all the bluff and bluster, Wagner’s finest proved quite limited when under fire. But it was not only Russian reputations at risk, so too were Russian relations with Haftar: spats were regularly taking place at the front, and Haftar had even stopped his payments to Wagner.

So, Moscow abandoned Haftar to suffer the consequences of his prideful intransigence. The Kremlin, as always, continued to deny any control over Wagner. But Wagner’s subsequent moves against Haftar (its purported employer), to secure what would become key strategic interests for the Russian state, show once more how the group was the handiest of tools for those leaders in Moscow who denied all knowledge of it.

A slippery symbiosis

As Haftar’s war was gradually lost, the Kremlin worked diplomatically to secure a favourable geopolitical environment for Wagner’s activities on the ground. The group’s hold over the disinformation space likely helped support the Kremlin in this geopolitical gaming. Back in 2020 there was little media, expert or political commentary covering Russia’s role in Libya, its use of foreign mercenaries or Haftar’s weakness. Much of the analysis at that time, in English and in Arabic, focused on Turkey: its “invasion” of Libya and its deployment of Syrian “terrorists”. This commentary also tended to overestimate the LAAF’s military potency.

Moscow thus harnessed Haftar’s and his backers’ growing dependency on Wagner to engineer an existential battlefield crisis for the ageing field marshal. Under the cover of the unravelling chaos, Russia first secured its existing interests. It then re-oriented the international alliance around Haftar towards a new diplomatic endgame for the war. Finally, it used its presence around Haftar’s bases and oil interests to make him dependent on Russian forces as his last line of protection.

Losing the war

After Turkey helped push Haftar out of Tripoli in April 2020, the UN and European states called for a Ramadan truce. The Kremlin pounced on this opportunity to try out a fresh political angle. This time Russia opted to elevate the speaker of the House of Rrepresentatives, Aguileh Saleh, as a new political figurehead for eastern Libya. This pivot seems to have taken place just as Wagner began its initial steps to withdraw from western Libya.[11]

On April 23rd Saleh proposed an immediate ceasefire and the creation of a new “presidency council”, shared between him and representatives from southern and western Libya. This council would then agree to form a new government. Despite a leaked video in which Saleh informed tribal delegates in eastern Libya that Russia wrote the proposal for him, European states and the UN backed the proposal as a political solution to a war that seemed to be slipping away from their influence. Egypt and the UAE, however, were not ready to abandon Haftar and pushed him to publicly reject the proposal. The field marshal duly obliged. He also announced the dissolution of the political agreement that had formed the house of representatives and declared military rule (much to Moscow’s chagrin).

On May 18th a phone call between Putin and Erdogan seemingly led to an agreement that Wagner would withdraw from western Libya. In return the GNA would not invade eastern Libya,. At that point, Wagner withdrew from western Libya in earnest, falling back to Jufra and Libya’s oil installations.

Just a day later, the GNA and Turkey humiliatingly forced the LAAF out of the al-Watiya airbase in the country’s west. Russia had deployed forces to the base when it first arrived on the front and intended to keep control of this large strategic stronghold. But relentless Turkish drone attacks destroyed three Russian Pantsir-S1 air defence batteries in quick succession and made that untenable. This was a humiliation for Moscow and Wagner, as GNA troops paraded Russia’s much vaunted Pantsir around western Libya. They then handed the captured missile system over it to the US.

Wutiya was the loss that began the chain reaction which finally ended the war. It triggered an initial escalation between Turkey and Russia: Russia sent advanced jets into eastern Libya (six Mig 29s, two Sukhoi 24s and two Su-35s); Turkey held large air exercises over the Mediterranean that featured its US-made F-16s. But Russia’s aircraft were not deployed to attack the Turkish air-defences in Libya or on other such sorties that might have altered the course of the war. This suggests Moscow was not challenging Ankara but merely moving in assets that would help it control the endgame.

Wutiya was also the final straw for the UAE, which finally relented and gave up on Haftar. The government in Abu Dhabi seemed satisfied with Russia’s vision: hold a new front line that guaranteed control of most of Libya’s oil and advanced Saleh’s process as a political vehicle for consolidation, while protecting and reforming the LAAF.

Indeed, Moscow instrumentalised the war via its presence in Syria to broaden its partnership with the UAE. Syria, for example, was the front through which the advanced aircraft were transferred, again disguising any Russian or Emirati culpability for violating the arms embargo. Moscow also used Russian-cultivated pro-Assad Syrian militias such as Liwa al-Quds to recruit mercenaries to secure Jufra and the oil crescent. This Libya collaboration helped facilitate Abu Dhabi’s early outreach to Assad. To divert Turkey from the Libyan front, for example, in April 2020 Emirati leaders allegedly considered sending the dictator $3bn to break the ceasefire in northern Syria and attack Idlib. It also deepened the UAE’s involvement in Sudan, as Emirati private security firms allegedly press-ganged Sudanese men into Haftar’s limping army.

As part of its pivot to lead on a new political settlement for Libya, the Kremlin also reached out to the GNA. The target was Fathi Bashagha, a former contact of Kadyrov’s who had since risen in prominence as the GNA’s minister of the interior and a key leader in Tripoli’s defence. But Prigozhin lobbied hard against this—as he held Bashagha responsible for the continuing incarceration of the electioneering operatives who were arrested in 2019. Wagner’s disinformation team had made a bogeyman out of Bashagha as a terrorist leader. He even featured as the villain of Russian feature films that were produced to drum up domestic support for the release of the jailed operatives. This diplomatic and military discord was also a legacy of Russia’s initial scoping exercise in Libya, underlining both the benefits and the drawbacks of the Kremlin’s policy to foment domestic competition in its outreach with prospective partner countries.

Eventually, the Kremlin settled on Libya’s foreign minister Mohammed Siyala. Far more consequentially, however, it also targeted Ahmed Maitiq, who was also a commercially influential deputy of Sarraj’s from Misrata. On June 3rd Maitiq, Siyala and Russian officials discussed an immediate ceasefire and peace process based on Saleh’s initiative that would have resulted in the resumption of oil exports, and the return of Russian companies to Libya. This would not be the last time that Maitiq returned from Russia with a controversial plan (see “There will be blood” chapter).

The Russia-Haftar alliance tried to draw the peace lines on the status quo ante positions of April 2019. But this split the GNA. Bashagha, who represented the majority position of the GNA’s armed forces, was adamant they needed to reclaim Sirte and Jufra as a security guarantee. He therefore tried to lobby the US and Europeans on the threat of Russian entrenchment at those crucial crossroads. But Wagner’s defences would make any assault a costly endeavour that GNA forces could not afford without Turkish support.

Egypt was the last piece of Moscow’s diplomatic puzzle. The government in Cairo understood the difficulties of Haftar as a partner, having been against his assault on Tripoli all along. But it also feared that the authoritarian framework it had helped Haftar build in eastern Libya through Operation Dignity would crumble without him. And, like many an abused partner, it probably still believed it could change him.

After the Wutiya debacle Haftar had gone to Cairo like the prodigal son, pleading for Egyptian military support to salvage his operation. Sisi refused to meet with him. On June 5th GNA forces began what was mooted to be a tough battle for Tarhouna, Haftar’s last stronghold in western Libya. The widespread belief among diplomats, commentators and even some military staff that this would be a long, messy battle—very likely linked to Wagner’s propaganda efforts.

But a mere 24 hours later GNA forces had routed the LAAF almost 400km to the east and were entering Sirte, where they discovered Moscow’s red line. They were met with a series of precision airstrikes, pushing them 100km out of the city, but not causing overwhelming casualties. This was likely a strategic move to not provoke the GNA and Turkey to double down on taking Sirte.

The next day Wagner moved into Sirte, locking down Ghardabiya airbase and Sirte airport and shelling the Wadi Jaraf valley that leads to Jufra to drive out its civilian population. The fleeing families pleaded with the LAAF to intervene, but it was powerless to stop Wagner—which needed Sirte as a buffer to protect its domination over the oil crescent and control of key military bases like Jufra. The bombardment continued for days until the area was clear, after which Wagner forces placed mines on the roads, set up air defences and built barriers out of sand to create a buffer around Sirte.

Russia had unilaterally drawn Libya’s new dividing line.

Again Putin and Erdogan agreed to stop the fighting on the newly settled lines, with Putin allegedly threatening an escalation in Syria should the GNA attack Sirte.[12] This was a Turkish-Russian pact that would be announced on Haftar’s side in Cairo, and then become formalised in a UN-sanctified ceasefire agreement on October 23rd 2020.

Haftar ended the battle, and the war, alone and broken. The entire western front had collapsed. His tribal alliances had been eroded, the LAAF was an empty shell, and the ageing field marshal was cowering in Cairo, begging for the protection of his founding partner.

Shaping the peace

In the aftermath of Haftar’s war, an UN-convened committee was tasked to elect a new prime minister and president for Libya. That duo would organise national elections by December 24th 2021. Russia allegedly worked behind the scenes as a bridge between Cairo and Ankara to construct its dream team of Saleh (Russia’s guy) as president and Bashagha (Turkey’s guy) as prime minister. With that, Moscow’s status in Libya would have been secure.

Indeed, the June 6th “Cairo declaration” from which the roadmap grew looked an awful lot like an evolution of the Saleh-via-Russia proposal from earlier in 2020. It was a solution that synthesised the paternalistic Egyptian belief that the dissolution of the LAAF could lead to Libya’s disintegration with Russia’s tactic from 2017 to legitimise its proxies through a political process.

The announcement included existing propagandistic narratives, such as labelling the LAAF as Libya’s national army and framing it as a counter to the “regional threat” posed by Turkey’s “invasion”. The declaration thus conveniently absolved Haftar’s forces and his international coalition of any accountability for the war they started. Beyond that, the agreement premised the ceasefire on GNA forces surrendering all their weapons to the shattered LAAF and called for foreign mercenaries to leave Libya; but it failed to mention Wagner. Nor did it mention Wagner’s detachments of press-ganged Syrians, the Sudanese Janjaweed militias from Prigozhin’s burgeoning relationship with the RSF, or the Chadian anti-government rebel groups that Wagner and the LAAF often employed. Underpinning this was a quiet understanding between Russia and Egypt that Haftar would later retired and the LAAF resurrected under a different Qaddafi-era officer.

Nonetheless, its presentation as almost an Arab-nationalist project quickly won it support from multiple Arab states. Egypt and the UAE then talked key Western states such as the US and Britain into backing it. (France needed less persuasion as a longstanding member of their coalition in Libya.) According to diplomats working on Libya at the time, Western leaders bought into the narrative of their Arab partners that this was the only way to avert a long war in eastern Libya and Turkey’s colonisation of the country.[13]

But Egypt still wasn’t quite ready to let go of Haftar. Cairo worked to repair ties between Saleh and Haftar to create a powerful eastern bloc able to influence the UN process. This international feeding frenzy to shape the process ate away at its integrity. Over the end of 2020, a deeply corrupt round of horse trading took place over the leading positions for an empty roadmap. To many observers’ surprise, the dream team lost the war of bribes—with the ever-mercurial Haftar disappointing Egypt once more as he flipped to support the man who would become prime minister, Abdul-Hamid Dbeibeh.

The December 2021 election famously did not happen as Libya’s political elite scrapped to take full control of the ill-defined electoral process so they could engineer it in their favour. In the run-up, Russia extended limited support without picking sides to all of its onetime proxies, Saif, Haftar and Saleh (who all ran for President).

Wagnerfication in the roscolonial

Between 2019 and the end of 2020, European influence in Libya and relevance to Libyan politics plummeted—displaced by Russia and Turkey. While Russia had undermined Europe diplomatically in the pre-Tripoli era, in this period it worked through Haftar as a “best of a bad bunch” proxy to entrench itself in Libya and build its political and military influence.

Russia showed a rationality about picking a proxy and building influence in Libya that contrasted with the often ideological or highly abstract approach of its Western counterparts. France and the US backed Haftar under a flawed analysis of him as a military strongman; Wagner coldly assessed him as unreliable and tried to juggle two bad choices in Haftar and Saif. At the UNSC the Kremlin helped to protect Haftar’s war, likely so that Russia could benefit from the chaos it left in its wake. But the Kremlin not only rendered Haftar dependent on Moscow; his regional allies such as the UAE also came to need Russia’s military assistance.

This approach has echoed in other theatres. The discrepancy between Russia’s cold pragmatism and Europe’s ideological approach was evident in Niger when President Mohamed Bazoum was displaced by a Russian-backed military coup in 2023. Bazoum was a democratically elected leader with Western support. But Russia played on public discontent, again building a formidable disinformation machine that spins a paranoia that now protects the military junta. In Libya, Niger and elsewhere, Europe’s resources would have been well-spent strengthening the information space: for instance, expanding the presence of news institutions into new forms of media and producing a stream of reliable, consistent content that would have pre-emptively filled the void into which Russia eventually surged.

However, the frailty of Russia’s approach is reflected in its initial points of frustration with Haftar. That is: the Kremlin struggled to convert its military cutting-edge into decision-making authority or contracts. This is likely why it sought once more to formalise its authority by brokering the 2019 deal with Erdogan; just as it tried to do in 2017, before Macron beat Putin to a summit.

Nevertheless, Russia’s ability to deploy a complex and effective set of diplomatic, political and military tools to protect Haftar showcased their value to the UAE, which clearly needed some operational assistance in bringing its foreign policy visions to life. It sparked a relationship that would continue through Sudan and the Sahel. Russia was not just setting a new pace in Libya; through its disinformation networks it had managed to shape how Western audiences and even Western policymakers were discussing the conflict, adeptly moving the spotlight from its mercenary forces to Turkey.

In turning away from Haftar, Russia then strengthened relations with key political players across Libya and domesticated the once-troublesome field marshal. This relegated the LAAF to a vehicle that provided cover for Wagner without being able to hinder its activities. LAAF staff were not even allowed to access Russian sites such as Jufra without Wagner’s approval. Although they have been less able to do this in other theatres since, Russia’s rapid spread through the Sahel has been accompanied by many tales of dominance and political prowess that shape thinking across the West even as Moscow struggles to entrench as effectively in countries like Mali or Burkina Faso as they did in Libya.

Domestication: How Russia taps into weak-state opportunities

Narcos Libya

The Dbeibeh debacle was undoubtedly a setback for Russia. Just as well Prigozhin had been cultivating a backup: the field marshal’s son, Saddam Haftar. And it was with him that Wagner worked to rebuild Khalifa Haftar’s shattered force and ensure it served Russian interests. Charting how this new beast grew shows how little Russia’s fundamental goals in Libya had changed over the years. They remained: establishing influence and a military foothold in the eastern Mediterranean; making money to fund Moscow’s adventurism; and developing a migration “trump card” against Europe.

Several driving forces led to the expansion and professionalisation of Libya as a smuggling hub, and Wagner as a likely partner for the Haftars in this development.

Scratching backs

First, it seems that Wagner and the Haftars managed to find a common cause. Having withdrawn from western Libya, Wagner still needed to consolidate control over the central oil-gateway city of Sirte. And Khalifa Haftar needed foreign military support to maintain his position as eastern Libya’s leader, having lost political and tribal support in the east. The LAAF would have to end up in his family’s and Wagner’s hands.

But Libyans are fiercely independent—and the idea of the removal of all foreign forces contained in the ceasefire agreement was genuinely popular. Turkey had some cachet in western Libya, having saved the day, but the sight of Turkish flags on Libyan soil would likely have sat uneasy with many. In the east, long-running propaganda about Turkey’s intervention as a neo-Ottoman violation of Arab sovereignty provoked a sharp rejection of its presence. Wagner, meanwhile, had sparked public outrage due to its forces’ Islamophobic attitudes and their abuses of civilians—not to mention the heinous crimes they had committed as they retreated from Tripoli, such as booby trapping homes and children’s toys. Even the LAAF officer class wanted Wagner forces to leave following their fallings-out during the war.

The atmosphere on the ground was tense: Haftar had promised the tribes of central Libya a new age of power and riches if they backed his assault on Tripoli. But their homes had instead become the front lines of a new conflict. Protests regularly broke out in Sirte and across central Libya calling for Wagner and its Sudanese mercenaries to leave. New social movements also sprung up; the Sirte Reconciliation Committee, for instance, whose aim was to repair ties with western Libya in order to defuse tension and expedite demilitarisation. Wagner would need a local infrastructure to clamp down on such upstart attempts at Libyan self-determination.

In Sirte the Tariq bin-Ziad (TBZ) brigade commanded by Saddam Haftar rallied the large Salafist and tribal components of its local deployment to control the city, even arresting the prominent head of the reconciliation committee. Another of Haftar’s praetorian brigades broke up protests across central Libya through a mass arrest campaign.

Drawing the trump card

Second, Wagner’s and the Haftars’ mutual need to consolidate power seems to have dovetailed with another perpetual need: money. Following the post-war consolidation it was Saddam Haftar who gained oversight over key airports like Benghazi’s Benina, and seaports in Benghazi and later Tobruk. In 2020 Cham Wings started a twice-weekly commercial route from Damascus to Benghazi’s Benina airport, intermittently advertising these as “migrant flights” on its Facebook page.[14] The conditions of obtaining security clearances and entry visas from Cham Wings offices connected the company to the dark new network of human trafficking that was growing under Saddam Haftar’s management.Haftar exploited the cross-country nature of his TBZ brigade to create a human smuggling infrastructure that transnational trafficking and smuggling networks could rent. For the price of a “racket fee” these networks were granted the use of one of Haftar’s nine entry hubs into Libya.

And the smuggling continues to this day. On arrival, migrants hand over their informal visas to the LAAF, who detain them until they receive payment by the network. They are then held for between several days to several weeks, typically in inhuman conditions, before being taken to “launch points” where they board boats towards Europe. At this point, Saddam is paid again for his coastguard units to allow boats through: $100 dollars per migrant for “smaller boats” (of around 300-550 people) or an $80,000 flat fee for larger boats. Others are taken to western Libya. This demonstrates how Libyan armed groups cross political divides in pursuit of profit.

Africans usually arrive in Libya via land borders. But a range of other nationalities from as far afield as Bangladesh arrive through the Cham Wings network. South Asians, paying up to $9,000 for their “visa”, fly to a transit point (often Dubai) where they receive these tickets in exchange for their liberty. They are then flown to Syria, where they are joined by Syrian migrants (paying lower fees of around $2,000) and onto Benina airport where they enter Haftar’s network. From January 2021 to March 2022, there was a 79% increase in Cham Wings flights. This was a period of relative military stasis in Libya, meaning this growth is likely attributable to smuggling. During this time Cham Wings ran at least 187 flights, carrying a maximum of 32,538 people,[15] while migrant arrivals from Libya to Italy rose by roughly 21,000.

Wagner had been busy developing a close relationship with Saddam Haftar and his TBZ brigade since at least end of the war on Tripoli. And its operatives have been spotted alongside TBZ deployments across Libya, most notably around smuggling hotspots along Libya’s south-eastern and south-western borders.[16] The involvement of Cham Wings, heavily used by Wagner for military purposes, sometimes running through Russian military airbases in Syria, also used to take migrants from Damascus to Minsk, is another indicator of how deeply Russia is likely involved in the Libyan operation. The Kremlin has weaponised migration elsewhere too since the all-out invasion of Ukraine, notably via Belarus towards Finland and Poland. Russia even seems to have turned Libya’s migration weapon towards the US in its fractious 2024 election year. Reports indicate that an additional stop was added to the migration airbridge with flights heading from Benina to Nicaragua.

But the Saddam-Wagner smuggling nexus was not limited to people. From 2017 onwards Libya had developed into a centre for drug smuggling; largely of hashish and captagon from Syria. The relationship with Assad was initially managed on the LAAF side by another tribal relative of Haftar’s, Fawzia al-Ferjani. Logistics and transportation was overseen by Mahmoud Abdullah Dajj with a shipping company headquartered in Latakia in Syria (conveniently where Russia’s headquarters in the country was also located). Daij is a Syrian-Libyan dual national who was sentenced to death in-absentia by a Libyan court for drug smuggling in 2019. That same shipping company, Al Tayr, is also the “exclusive” agent that started organising commercial Cham Wings flights from Damascus to Benghazi from October 2020.

Neighbouring sounds

Finally, the network also seems to have ambitions in Libya’s neighbouring countries. In December 2020 the TBZ deployed to south-western Libya. There Haftar’s unit entered into a low-burning series of skirmishes with GNA-affiliated forces to gradually claim control of the city and region, relying on intelligence, logistical and surveillance support from Wagner operatives stationed nearby in Brak al-Shati military airbase[17]. The oasis city of Sebha is notable as a crossroads for smuggling routes from Chad and Niger into southern Libya, as well as gold that is mined in southern Libya and the Tibesti mountains just across the border in Chad.

In September 2021 the TBZ again deployed. This time it was against the remnants of Chadian opposition group FACT (which had previously fought alongside Haftar in 2020, based out of Jufra). Back then, Wagner distrusted the group because of its close relationship with France,[18] and now the group was licking its wounds after a failed attempt to invade its homeland earlier that year. The TBZ struggled, suffering significant casualties over a four-day battle. But laser-guided artillery and airstrikes of foreign origin allowed Saddam Haftar’s alliance to significantly degrade FACT’s force. The rebel group blamed France for providing this foreign support. But it is more likely that it came from Wagner. Airstrikes from Jufra would have been easier to deploy and conceal than any French activity, and Wagner had experience working with the LAAF as spotters for guided artillery during the Tripoli war.[19]

This operation could also be read as initial alliance-building from the Emirati-Russian coalition with Chad’s new dictator, Mahamat Déby, the son of the former autocratic president Idriss Déby who had been killed by rebel forces during the recent incursion. This coalition’s relationship-building with the new president would eventually displace France in N’Djamena and lay the ground for Chadian support for the RSF in Sudan as Russia found the opportunity to pursue its “first approach” once more in Chad. Whatever the aims, when the battle ended, the TBZ with Wagner was able to enforce greater control over the region’s smuggling routes. This bolstered its revenues from people and drug smuggling, and Libya’s gold mining. Most of all, however, it enabled fuel smuggling.

There will be blood

Wagner’s modus operandi was always to lever its military support for frail dictators against a nation’s assets. By 2020 this model was already well-established in Syria and the Central African Republic. But no Wagner target-state ever had quite the resources of Libya; nor quite the international congestion around it. Libya underwent Moscow’s most sophisticated example of asset hijacking, as the country became a chip in the Kremlin’s efforts to squeeze out geopolitical rivals and eventually evade international sanctions.

Securing the bag

When Wagner then abandoned Haftar on the Tripoli front from May 2020 onwards, it did not just fall back to secure Jufra and other military bases. It pre-emptively claimed Libya’s oil installations. Wagner operatives and Syrian mercenaries (flown in by who else but Cham Wings) moved into the Ras Lanuf refinery and the oil crescent’s export terminals; seizing worker housing, large quantities of aviation fuel, and installing powerful S-300 air defence systems.

Simultaneously, other Wagner units alongside Sudanese mercenaries secured oil fields in the south, notably Libya’s largest field al-Sharara, reinforcing an oil blockade that had begun in January 2020.

This control over oil flows gave Russia the cards for its failed solution to the conflict. As the ceasefire that followed the Cairo declaration slowly fossilised, Europeans and Americans tried to transform a misshapen ceasefire of necessity into a more sustainable peace. Moscow, for its part, flexed its control over Libya’s oil. Not only did it continue enforcing the 2020 blockade to shape negotiations, but it used its position to pre-emptively move against an American initiative with the UN and the NOC that would have led to the demilitarisation of oil sites.

In September 2020 the Kremlin snuck one of its GNA assets Maitiq (the Sarraj deputy mentioned in the “Losing the war” section of this paper) to a Russia-Africa summit in Sochi. He was joined by Khaled Haftar, who had been given military responsibilities and designated the official interlocuter for Russia as part of Haftar’s post-war consolidation. In Sochi, Russia brokered a deal that would see oil exports resume and a new committee formed to manage and distribute oil revenues between eastern and western Libya. The deal outraged the elite in western Libya. Sarraj and key financial players such as the central bank governor rejected it as opaque, illegal and favouring Haftar. Maitiq, who had no authority to make such a deal, was blocked from going to Sirte for its signing ceremony. Despite this, the mere existence of the rejected deal now meant the GNA and NOC looked like the bad guys.

This pressure worsened as the US, UN and key European states pushed Libyans to accept the Sochi deal as an important step towards stability, a permanent ceasefire and new political process. But acquiescing to this deal represented nothing of the sort. Rather, it legitimised the divvying up of Libya’s oil wealth and was the first major chip in the NOC’s integrity.

It was also a boon for Russia’s stature in Libya and provided another stream of funding to help reconstitute Haftar in the east after his defeat. Finally, it meant the UN and the West had discarded perhaps the strongest leverage they had to expel Wagner from Libya’s oil sites. They had also given Russia a pretext for future shutdowns—since the full administrative provisions of the deal could never have feasibly been implemented. As with the Cairo declaration, embracing the Sochi deal happened under the illusion of securing a short-term stabilising win that the UN could improve later and despite warnings from Libyans. The oil flowed once more. But Russia retained control.

Flexing control

In the spring of 2022, a couple of months after Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine, oil prices were rocketing and Europe’s energy crisis was already well under way. Meanwhile Libya’s political divisions had worsened in the wake of the 2021 electoral debacle. Dbeibeh, the internationally recognised premier, had outlasted his mandate, as the elections he was appointed to oversee failed. This led the House of Representatives to appoint Bashagha as prime minister in a deeply flawed process (that would have installed half of the Turkish-Russian dream team for 2020 into power). But Dbeibeh exploited the procedural violations to cling on to power. Then on April 18th Libya’s oilfields, then its oil terminals, began to shut down. This was framed by Haftar-aligned media as a popular protest against Dbeibeh’s unwillingness to cede to Bashagha. But it was an LAAF operation that could not have happened without the support of the Wagner operatives camped at these installations.

The shutdown cut off key Italian and other European refineries from a major source of energy supplies. Shortly after the oil blockade, the chair of the NOC sent a letter to Libya’s chief prosecutor asking him to take action against the fuel-smuggling tankers. But the blockade went on for three more months until the UAE negotiated a breakthrough deal between Dbeibeh and Saddam Haftar. The terms of this deal were that Haftar would switch the oil back on, but he could appoint a new chairman of the NOC and would get additional funding from the body. This was the natural evolution of the Sochi deal: it again exploited the crisis of an oil blockade to solicit huge financial and structural concessions for Haftar at the cost of the structural integrity of both Libya and the NOC.

The new NOC chair, Farhat Bengdara, was a former central bank governor with no experience in the oil industry. According to those familiar with the deal, he was appointed as a result of his financial expertise. [20] Alongside this change, $6bn was released by the Central Bank of Libya, ostensibly as financing for the NOC. Yet it seemingly ended up moving through a subsidiary to Saddam Haftar who then allegedly used it to pay Wagner. Within a year, Saddam’s loyalists were appointed to management positions over key subsidiaries, most notably the Brega Company that was responsible for all of Libya’s fuel imports.

Priming the pump

Alongside these structural changes, a massive fuel smuggling scheme between Saddam and Russia took off, which the new NOC tried to mask.[21]

Moscow needed Libya to bypass Western sanctions on Russian fuel exports. Russian petrol and diesel exports into Libya suddenly exploded in September 2022, rising from sporadic shipments of a few thousand barrels per day (bpd) delivered over several months to almost 20,000 bpd that month alone. Russia did this covertly, with Turkish companies often acting as brokers. By spring 2023 the exports had reached almost 90,000 bpd, exceeding 100,000 bpd by January 2024. (They only declined after that as Ukrainian attacks on Russian refineries increased.) Russia exported $2.6bn worth of fuel to Libya, making it the largest seller of fuel and covering 28% of all the country’s imports (up from 4% in 2021).